History Of Surfing: But Will It Play On The East Coast?

Re-post From Surfer Magazine online

Why the ’60s surf boom exploded loudest out east

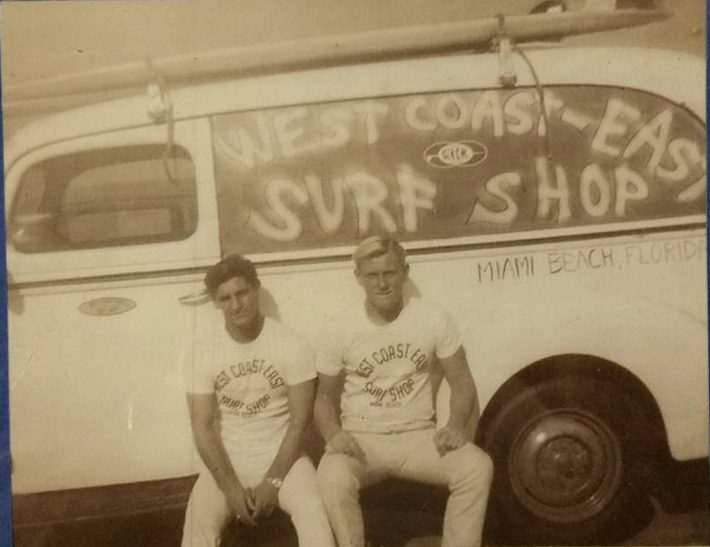

America’s top-selling board of the ’60s was not from the quiver of a West Coast superstar; it was the Hobie signature model of Floridian hotdogger Gary Propper. A sleek noserider with a concave, teardrop pattern shaped near the tail, the board made up half of the 6,000 surfboards that Hobie shaped in 1967, almost all of those sales coming between Maine and Miami Beach, FL. The U.S. East Coast received the ’60s surf boom more enthusiastically than perhaps any other coastline in the world. The legacy began as early as 1912, when The Duke arrived in New Jersey for his surfing exhibitions and opened the eyes of spectators to the diverse set-ups along the Atlantic Ocean. 50 years later, the East Coast was its own factory of champion talent, particularly in Florida, where names like Propper, Mike Tabeling, Dick Catri, Mimi Munro, and Claude Codgen inspired a new, original East Coast pride. Here’s History of Surfing‘s Matt Warshaw on the early years of the Right Coast boom:

The 1960s surf boom can be parsed in a lot of different ways. The West Coast got busy inventing the surf industry, Australia was springloaded to become the most progressive wave-riding nation on earth, while surf fever went airborne and touched down on beaches from Sao Paulo to Christchurch. But based on demographics alone, the boom exploded loudest on the American East Coast. In 1959, there were maybe 250 dedicated riders between Miami and Cape Cod. By 1966, the East and West Coast surfing populations were nearly equal, at about 200,000 each. More than 10,000 spectators attended that year’s East Coast Surfing Championships, 70% of Hobie Surfboards made that year were shipped back to Atlantic Seaboard dealers.

Coastal geography had a bigger impact on the sport’s development in the East than it did in the West. America’s Atlantic shoreline is half-again longer than it is along the Pacific, and East Coast surfers were pretty evenly distributed from north to south. By comparison, roughly 95 percent of West Coast surfers in the mid-1960s lived in a compact two-hundred-mile beachfront corridor between Santa Barbara and San Diego. There were cultural differences, too. Santa Cruz was colder than La Jolla, but otherwise not drastically different as a surfing region. It all felt like California. Georgia’s humid sandbar peaks and the lobster-encrusted coves of Rhode Island, on the other hand, seemed to belong to different planets–as did the local surfers.

By the same token, West Coast surf history could be traced back almost exclusively to a single first surfer, George Freeth. The East Coast has no singular surf history as such; rather, it’s a bundle of histories. Locals often got things started. The pencil-thin Whitman brothers of Miami, Bill and Dudley, rode homemade wooden bellyboards in the early 1930s. Twenty years earlier, the Virginia Beach summer resort crowd lined the boardwalk and applauded as “Big Jim” Jordan cruised shoreward on his imported Waikiki plank. (On the Gulf Coast, a deaf lifeguard named LeRoy Columbo–later cited in the Guinness Book of Records as the “World’s Greatest Lifeguard”–took on the muddy brown rollers of Galveston in the early 1930s, and earned a few bucks on the side by renting out a pair of special Firestone-made surfboards built from inflated rubber tubes wrapped in heavy canvas.)

[READ THE FULL HOS CHAPTER HERE. NOT A SUBSCRIBER YET? SIGN UP HERE.]

We asked Warshaw more about the East Coast, about Gary Propper’s rise to national fame, and more.

In an interview you did with Gary Propper in ’84, he said, “I never went to Australia. I never really went anywhere back then. I wanted to be strictly East Coast. Nothing else. I knew I was going to just kill it there.” How much of the boom does that mindset explain — that East Coast surfers were discovering the opportunity to be the big fish in their own pond? Or how much of that was just classic Propper?

That’s just Gary. Business-wise, he was thinking so far ahead of any other surfer at that time. Or any time. Gary was, and still is, incredibly smart, off-the-chart ambitious, and had the energy of a speed freak without actually being one.

There are stories of Propper chucking second-place trophies into the bushes, and he was often a sore, flamboyant loser. Some of that was born from the relatively meager waves conditions — an appreciative mentality leads to a scrappy mentality, which lends well to man-on-man heats. How did East Coast surfers fare in national competition during the boom?

Gary could have been US champ in 1966, 1967. Corky Carroll and David Nuuhiwa were the guys to beat, and in small waves, if those three paddled out together–I’d put my money on Gary.

The Whitman brothers, Big Jim Jordan, LeRoy Columbo — the locals who started the scene in their communities sounded less like celebrities and more like folk legends.

East Coast surf history is so different from West Coast surf history, in that none of it really connects. In California, you more or less have George Freeth alone there at the bottom, in Los Angeles, and it flows up to Blake, then Simmons, all the way to the Coffin brothers. In the East, surf history is a package deal, a bundle of local surf histories loosely tied together. Less attention gets paid to the early guys, because there are so many of them.

You mention in your chapter that the reasons are unclear, but why do you think that surfing didn’t immediately rebound in the postwar years like it did on the West Coast?

Probably because beach culture in general was way more of a thing in California than it was up and down the Atlantic. From San Diego to Los Angeles, going to the beach was already a tradition, an industry, an art form.

Around what time did the East Coast’s homegrown surf retail economy started to become its own, instead of being the second choice for California brands?>/strong>

Not long after the boards went short. I can’t think of any longboard-era brands from the East Coast that could hold their own with the imports. But by the early ’70s, there were some really great boards being made there–Wave Riding Vehicles, Full Force, Sunshine. There was a really embarrassing time when West Coast surfers, in their endless groveling to all things Hawaiian, were mostly riding full guns. As an 8th-grader, I rode a 7′ 4″ pulled-in diamond tail — at Bay Street, Santa Monica. We’re all pretending to be Jeff Hakman, so obviously we had to ride the same board Jeff used at Sunset. East Coast surfers in the early- and mid-’70s, as a rule, were on way better equipment then us.

His contributions are many, but what will Dick Catri be most known for, in your opinion?

Dick was a surfing pirate, for better and worse. A happy swashbuckler. The surf world only knows maybe one-tenth of what Catri got up to during his life, but my sense is that most of it was exciting, dangerous, funny, possibly illegal–and that he took all the best tales to his grave.

For more, visit the History Of Surfing website here. Missed a HOS chapter? Click here.

John Hannon, was the first to build boards on the east coast.

North Florida had its champions and innovators Larry Miniard, Bruce Clullend, Joe Roland (first 4A east coast champion), Diki RoZo Rosbourgh, to mention a few. We always gave the CoCo beach boys a run for there money. The surf scene in Jacksonville beach, Neptune beach, and Atlantic beach has never been stronger or more diverse. So when discussing East Coast Surfing you must include the small quite surfer town that made as important contributions as anyone else in surfing on the east coast.

Gotcha covered…

https://floridasurfmuseum.orgkahunas/jacksonville-surf-legends