Article by Neil Pearlberg (this article originally appeared in the Lookout Santa Cruz)

Mark Sponsler has gained cult status among big-wave surfers thanks to his ability to time a wave down to the minute and predict its height to within inches. The retired engineer’s website, Stormsurf, combines meteorological science with custom software to forecast exactly when the next monster wave will hit.

Mark Sponsler can tell you exactly when the next monster wave will hit Steamer Lane. Not just the day or the hour — he can predict down to the minute when these towering walls of water will arrive.

“I can paddle out at Mavericks when it is like a lake and know that within 30 minutes the first 15-foot wave is going to hit,” said Sponsler, referring to the legendary big-wave surf spot north of Santa Cruz off the shores of Half Moon Bay.

Sponsler, 67, runs Stormsurf.com, a website that has become an essential resource for surfers to track ocean conditions worldwide. His predictions draw from raw data downloaded directly from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s supercomputers, which he processes using open source software and custom-built scripts into detailed visualizations.

Mark Sponsler surfing Mavericks in Half Moon Bay. Credit: Curt Myers / Powerlines Productions

Most surfers track water conditions by visiting local cameras, websites or by cruising past their favorite break to check the surf. Sponsler’s gaze extends 2,400 nautical miles west of Santa Cruz to the international date line. “That’s where all the action is,” Sponsler said.

He tracks typhoons as they form in the Pacific Ocean and head west toward Japan and the Philippines before being redirected by the jet stream.

During El Niño years, weakened Pacific trade winds allow warm water to flow eastward toward South America, shifting the jet stream over California. That can create what Sponsler calls “extra tropical storms” — massive weather systems that often generate 1,000-mile stretches of hurricane-force winds aimed directly at the U.S. West Coast.

“The further out you go to read the [weather], the more chaos and uncertainty you have,” Sponsler said. “Once the storm forms, and there are winds blowing across the ocean surface, I am able to time the incoming swell to within the first wave that is going to hit Mavericks.”

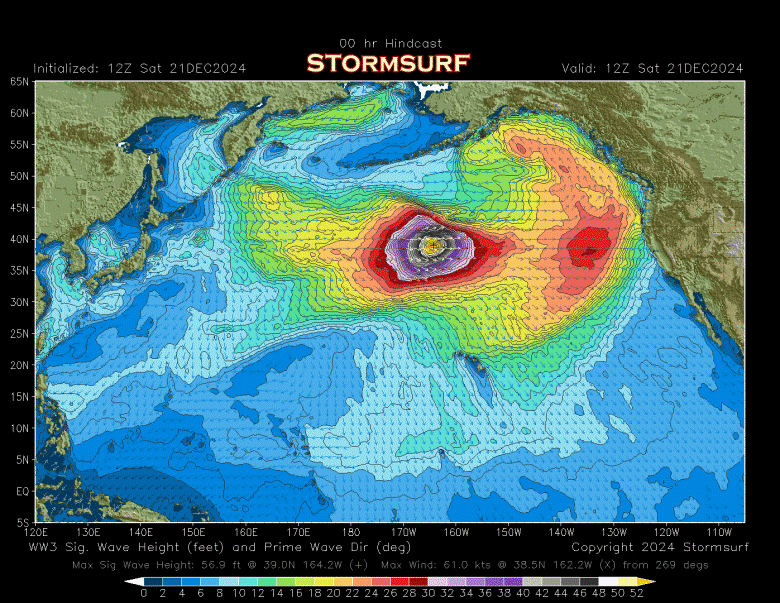

Last Saturday, Dec. 21, Sponsler’s Stormsurf was tracking a massive storm with 56-foot seas as it headed toward the Central Coast. Two days later, that storm caused huge waves, which damaged the Santa Cruz Municipal Wharf and forced the evacuation of Capitola Village and the Rio Del Mar neighborhood of Aptos.

A screenshot from Sponsler’s website, Stormsurf, showing a major storm with 56-foot seas just off the coast of the Western U.S. on Dec. 21, 2024. The storm would later cause huge swells that damaged the Santa Cruz Wharf and flooded sections of the county. Credit: Mark Sponsler

On Stormsurf, surfers can zoom in to see precisely detailed information, such as when the surf will arrive at Steamer Lane or Pleasure Point to within an hour and what the height of the waves will be.

“Mark is not only one of the world’s leading surf forecasters, he is also an excellent big-wave surfer,” said Jeff Clark, the veteran big-wave surfer who first discovered Mavericks. “I try to stay within his shadow because he knows the exact arrival time and wave height of an incoming Maverick’s swell.”

Grant Washburn, a big-wave athlete and filmmaker, said Sponsler is known for verifying his forecasts firsthand. “He is the only forecaster I’ve seen paddle out to see if his prediction of 50-foot faces is accurate,” he said.

From left to right, Rick Tubridy, Sam Steger, Sam Drazich, George Drazich, & Mark Sponsler of Stormsurf. New Smyrna Beach about 1971.

Sponsler’s journey to becoming surfing’s premiere wave forecaster stems from a childhood spent growing up on an avocado farm just outside Miami.

It was when an avocado ricocheted off the metal window shutters of his bedroom, caused by 120 mph winds from a Category 3 hurricane, that 7-year-old Sponsler first became fascinated with meteorology, the science of weather. He followed in his father’s footsteps, enthralled with the combusting energy in the atmosphere during hurricane season.

“My very first recollection was sitting in the basement of the farmhouse listening to the powerful winds that roared over our house like a never-ending express train,” Sponsler said. “Then total silence, to where my father would lead me outside to teach me about the eye of the hurricane that loomed over our small home.”

In the complete quiet that resembled a library, Sponsler would lie on the ground while his father, Leonard, would point to the stars in a crystal-clear night sky overhead. Then they would lower their eyes to take in the menacing dark wall of circular clouds surrounding them 10 miles in every direction.

Advertisement

“There was so much energy around the weather in the South,” Sponsler said. “It was visceral. You just could not ignore it when it happened, and I wanted to learn more.”

The family later moved to Cocoa Beach, three hours north of Miami, to a home just two blocks from where world champion surfer Kelly Slater lived.

Residing in a famed surf town, Sponsler’s passion for surfing grew, and so did his interest in forecasting the hurricanes that made the best East Coast surf. He began studying satellite images of weather patterns that would occasionally appear in the local paper.

After graduating from nearby Rollins College in 1980, Sponsler started working for Lockheed Martin’s space shuttle project at the Kennedy Space Center at Cape Canaveral, sticking thermal protection tiles on the orbiter. He later moved into the quality assurance department, where he validated the software that controlled the shuttle.

With the latest and greatest technology at Sponsler’s fingertips, a colleague introduced him to what would become his most powerful forecasting tool.

“In a day I won’t soon forget, my work colleague, David Groden, acting mysterious and dark, took me into a back room full of computers, sat me in front of a monitor that showed satellite photos, buoy data and ocean charts, and explained, ‘Mark, this is called the internet,’” he said.

His reaction was immediate: “Oh my God, this is the holy grail for a weather freak!”

Armed with this new technology, Sponsler headed to the West Coast, drawn to Half Moon Bay by the biggest wave of all breaks, Mavericks.

It was there, suitcases and boxes barely unpacked, that Sponsler began snooping around the then-sleepy coastal town and met Clark. The professional surfer shared stories about the monster wave just offshore, and the possibilities of forecasting when it might break.

Sponsler took advantage of the even better technology afforded to him being close to Silicon Valley and within a month he launched Stormsurf online. The site’s traffic quickly exploded from 30 views on its first day to 1,000 views after the first week. It was then that Sponsler realized he had come across something significant.

“It really started to snowball and I got sucked into the rabbit hole,” he said. “It became a daily routine to forecast big waves … not just at Mavericks but surf spots all over the world.”

Mark Sponsler in front of the home computer where he runs Stormsurf. Credit: Mark Sponsler

Sponsler recently retired as a software engineer and now spends about 15 to 20 hours a week working on Stormsurf from his current home some 40 miles from the ocean in Castro Valley. The site generates revenue from a mix of advertising, donations and from money Sponsler makes through weekly YouTube videos. However, it’s mainly a labor of love and a way for Sponsler to make new friends.

“I basically make minimum wage for my efforts,” he said. “But it’s more about doing what I like and doing it for the community.”

Over the years of tracking the world’s waves, Sponsler said he’s seen the intensity of storms in the Pacific Ocean diminish significantly. He attributes this decline partly to the growing prevalence of La Niña, the same weather pattern that has contributed to California’s recent droughts.

That shift could be driven by natural ocean cycles that repeat every few decades, or the effects of climate change — or some combination of the two. It’s “too early to tell,” he said, “but for sure this isn’t the same as the late ‘90s or early 2000s.”

When he’s not working on Stormsurf, Sponsler is surfing Mavericks at Half Moon Bay or San Francisco’s Ocean Beach in the winter. He spends summer surfing in Santa Cruz.

Next time you’re out on the water, watch for him — he’ll be the surfer who seems to be catching waves like he knew they were coming from thousands of miles away.

Mark Sponsler surfing Sewer Peak in Pleasure Point. Credit: Mark Sponsler

Leave A Comment