Ford founded the Outrigger Canoe Club in 1908, a place where Aloha prevails and “where the sports of old Hawaii shall always have a home.” (Image compliments of Outrigger Canoe Club)

The Hawaiians called him simply “Hume.” Alexander Hume Ford (1868-1945), magazine editor, playwright, photographer, unabashed campaigner and founder of Hawaii’s Outrigger Canoe Club, traveled widely in the Pacific Rim and promoted Duke Kahanamoku and George Freeth to an American audience. But he may best be remembered as the “guy who turned Jack London on to surfing.” If he is remembered at all. Duke Kahanamoku, with his Olympic and world-record stardom and surfing demonstrations, is widely considered to have been the ambassador who introduced surfing to the Atlantic Coast of the United States. But the real credit may lie with Ford.

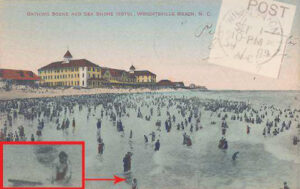

Recent research has raised the prospect that Ford, a native South Carolinian, was an earlier influence on surfing on the East Coast than was the Duke. Prominent surfing historian Joseph “Skipper” Funderburg, author of “Surfing on the Cape Fear Coast,” has come upon several early twentieth century postcards that prove what many global surf historians had only surmised – that surfing on the American East Coast was taking place in isolated pockets prior to Duke Kahanamoku’s surfing demonstrations in 1912 and 1916. Bearing dates as early as 1909, the postcards depict North Carolina’s Wrightsville Beach resorts and show young boys riding prone on boards whose “. . . plan shapes are almost identical to the ones seen in photographs of boards in Hawai’i at the turn of the millennium.”

But what accounts for the similarity?

By the early 1900s when Ford settled in Honolulu, the sport of surfing had been all but lost. The Hawaiian population had been decimated in the second half of the nineteenth century by diseases brought by Europeans, and if that weren’t insult enough, the Calvinist missionaries among them considered sports a waste of time and the pathway to moral depravity. But Ford loved to surf and was possessed by a passion to revive the neglected Hawaiian sport of kings. In May 1907, Ford introduced himself to Jack London, who was vacationing at the Moana Hotel on Waikiki Beach. London’s wife, Charmain, described Ford as an enthusiastic spokesman for surfing “for the benefit of Hawaii and her advertisement to the outside world,” and she characterized him as a “genius” at “pioneering and promoting,” who “swears he is going to make this island’s pastime (surfing) one of the most popular in the world.”

For a little context, earlier that month, Ford and George Freeth – who taught Ford to surf – had traveled the islands with a 28-member U.S. congressional delegation whose ostensible mission was to determine whether Hawaii could qualify for future statehood. Freeth acted as the delegation’s lifeguard, while Ford worked the politicians.

Meanwhile Ford, barely more than a beginner himself, offered to teach Jack London how to surf, and the next day he and Freeth kept London out For a little context, earlier that month, Ford and George Freeth – who taught Ford to surf – had traveled the islands with a 28-member U.S. congressional delegation whose ostensible mission was to determine whether Hawaii could qualify for future statehood. Freeth acted as the delegation’s lifeguard, while Ford worked the politicians.

Meanwhile Ford, barely more than a beginner himself, offered to teach Jack London how to surf, and the next day he and Freeth kept London out long enough to get him hooked on surfing and crisply sunburned. London described the experience in “The Cruise of the Snark” (1911):

“Ah, delicious moment when I first felt that breaker grip and fling me. On I dashed, a hundred and fifty feet, and subsided with the breaker on the sand. From that moment I was lost.”

London’s magazine article “Surfing: A Royal Sport,” published in October 1907, introduced the Western world to the sport of surfing on wooden boards.

In 1908, Ford founded the Outrigger Canoe Club, the first formal organization with a mission of preserving surfing. Ford petitioned Queen Liliuokalani for use of a tract of land on Waikiki to popularize old Hawaiian water sports and to provide a place to surf for the children of the mauka, the people who lived in the hills and had no seaside of their own. With a fifty-year lease at $50 a year, the club was founded with a grass shack for a locker room and an open-pipe shower with a coconut thatch shower curtain.

Although Ford’s club was for the mauka, when it opened it was restricted to haoles, white people from the mainland. So Ford urged the Hawaiians to start a club of their own. They organized the Hui Nalu Club, whose best swimmer was Duke Kahanamoku, and began to compete with the Outrigger Canoe Club. Kahanamoku’s world-record performances at the 1912 and 1920 Olympics paved the way for native Hawaiians to join, but when the Duke was invited, he remained loyal to Hui Nalu, stalling for nine years before finally becoming a member.

After establishing the Outrigger Canoe Club, Ford continued to promote surfing through various events, his writing and photography. He was one of the first photographers to capture action surfing shots, “perhaps, the first photographs of surfing ever to appear in magazines (St. Nicholas and Colliers).” And after Freeth moved to the mainland in 1907, Ford began promoting Duke Kahanamoku as “Hawai’i’s ‘Champion Surf Rider,’” years before the Duke gained fame as an Olympic swimmer.

Ford’s promotion of surfing extended wherever he went, it seems. In 1908, while in Australia assisting with trade agreements between Hawaii, Australia and New Zealand, Ford introduced surfing to an Australian named Percy Hunter, who just happened to be the head of the New South Wales Immigration and Tourism Bureau. By the time Ford visited again in 1910 – nearly five years before Kahanamoku went to Australia for the first time – “there were already several surfboards stashed at Manly Beach.”

The earliest known record of Ford’s promotion on the East Coast was in 1919, when he showed movies of Hawaiian surfing to the boys of Charleston’s Crafts School, South Carolina, and met with them to form an aquatic club. Surely a bit of evidence exists for Funderburg yet to unearth, proving the odds that Ford’s passionate campaign is to account for the images in those postcards.

If after you’ve read this article – and more of the excellent resources listed below – it is still Duke Kahanamoku and not Alexander Hume Ford who springs to mind when you think of the origins of modern surfing, perhaps that would have been fine with Ford. He viewed his job as doing the talking, and it is clear he got what he wanted.

Sources

Gault-Williams, Malcolm, Legendary Surfers Volume 2: Early 20th Century Surfing and Tom Blake (2007)

Sutton, Horace, Country Club in Hawaii, Sports Illustrated (Nov. 12, 1956)

Special thanks to Joseph “Skipper” Funderburg for bringing to our attention his discovery of the Wrightsville Beach postcards. Funderburg is the author of “Surfing on the Cape Fear Coast,” Slapdash Publishing (2008). He has been writing about surfing for 40 years and is recognized as the Cape Fear Coast’s preeminent surf historian. We hope you’ll seek out a copy of his book and read more about him at http://www.carolinabeach.net.

Julia Gilman, my paternal grandmother, was married to the brother of Atherton Gilman. Atherton was in that first gang of boys that Alexander Hume Ford crossed paths with in 1907 Waikiki. He asked them for surfing lessons and later approached Jack London, asking him if he’d like to learn how to surf.

Thank you for sharing that story! Hume was inducted into the East Coast Surfing Hall of Fame this year and I had the pleasure of meeting members of his family. It was a great honor.