Paul Holmes’ profile on Gary Propper ran in the November 1999 issue of Longboard magazine.

* * *

Before he even hit his teens, little Gary Propper was already a streetwise hustler. Growing up in a troubled single-parent family situation, he gravitated to amateur boxing at the local Boys Club in Miami, just a jab away from the famous 5th Street Gym where Angelo Dundee was training Muhammad Ali and other big name heavyweight pros of the early ’60s.

Propper snuck in to hang out with the pugilists (“badass motherfuckers” is how he describes them), as well as entertainment industry icons like Jackie Gleason and other old Jewish comics on winter respite from the Catskill borscht-belt circuit. It was there that Propper got a feel for the hard knocks school of humor, in the ring and on the stage—the real world of lives from the ghetto and the shtetl; the blood and guts and pain and joy of those who grew up on the wrong side of the tracks, with the wrong skin color, the wrong accent, the odd-sounding names, but who dragged themselves up by grit and bootstraps and pure determination to make successful lives as sports heroes and entertainers, publicists and managers, promoters, mavens and machers. As a small, blue-eyed, blonde kid (albeit of Jewish stock), the genetic odds were stacked against Propper in the Boys Club ring. He shouldn’t have had much of a chance against the Cuban and Puerto Rican boxers, but the feisty youngster held his ground, never gave an inch, even against guys much bigger and older than he was. Then again, by 11 years of age, he was already a successful entrepreneur: at night, after boxing, Gary would sneak under the chain link fence of a business that sold exotic birds, and steal a few parakeets to trade with the local burlesque dancers for semi-nude pictures of themselves. In the schoolyard the next day he’d sell the “pasty photos” to the highest bidder. Propper was never short of lunch money.

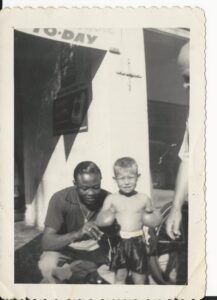

GP at 4 years old with Kid Gavilan, 5th street gym, Miami FL

Leap ahead 10 years, to when Gary Propper was the East Coast’s first major surf star, a key member of the stellar Hobie surf team, selling more signature model surfboards than anyone in the country during the peak mid-’60s surf-boom period. When it came to self-promotion and marketing prowess, Propper was relentless , intuitive, constantly in motion and highly successful.

Ten years after that, here’s Gary Propper re-inventing himself yet again—as an entertainment industry promoter, booking top-flight bands like Blondie and The Police into clubs and concert venues throughout the south.

Another 10 years on, he’s managing the comedian Gallagher, parlaying Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles into a movie and merchandising deal that nets mega millions, and promoting Carrot Top in the most glitzy showbiz rooms at Bally’s and the MGM in Las Vegas.

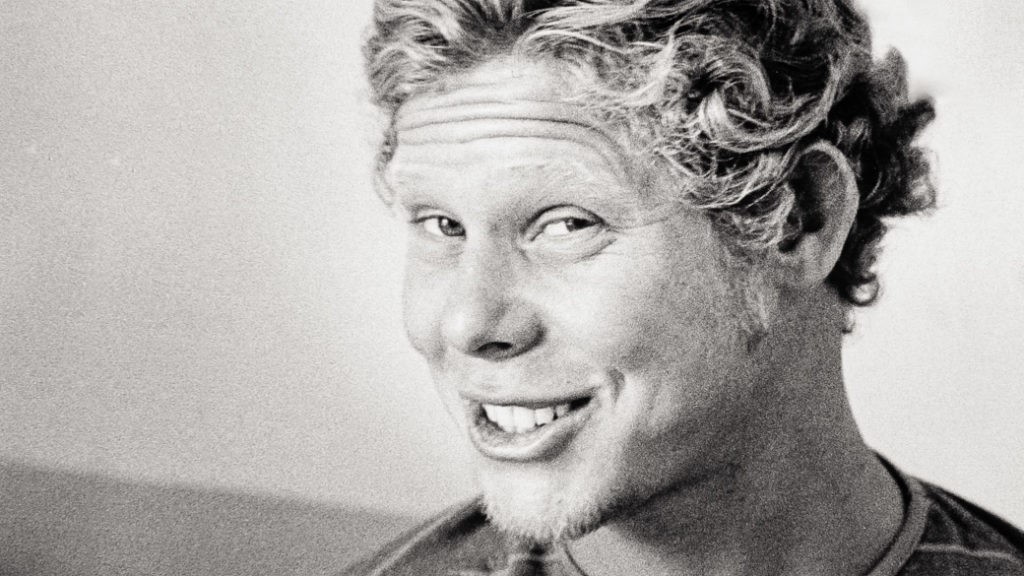

Gary Propper is rightfully proud of his achievements in life. At 53 he’s a mover and shaker in the entertainment business; a living, breathing, electrifying example of the American Dream—that anyone can rise from humble roots and become whoever they want to.

For much of his early life, Propper lived with his grandparents. “They couldn’t control me, I was just too hardcore,” says Propper today. “I liked being the little tough guy, it was cool. I dug beating up on the big guys. I was the little white kid in the ghetto.” And he adds, philosophically, “People talk about growing up in hard times but you never see it that way until you get out of it.”

That moment began in 1962 when Propper’s mother remarried and the family moved to Cocoa Beach. But the kid was still a handful. “I was terrible in school,” he says. “I fucken hated it. And I hated discipline.” Propper’s new stepfather, an attorney (and later a judge) at nearby Port Canaveral, didn’t fare any better when it came to keeping his new charge in line. “I didn’t realize it at the time,” reflects Propper, “but in Miami I’d been at the hub of what was happening in Florida. In Cocoa Beach I felt like I was in farm country. There was nothing here but a few bars. Cape Canaveral was the place—full of computer nerds in white shirts and black ties all looking for a piece of ass. It was the Cape that first started attracting tourists.”

The feeling of isolation gave young Propper pause to reflect. “I realized I was poor; that I had no social or home life,” he says. “When I didn’t do well in school my stepfather freaked out and started to mentally abuse me. It was fucked up. But he could never control me either.”

Alienated, tough, aggressive and punchy, Propper could easily have become just another statistic in the files of juvenile delinquency. But the accident waiting to happen finally occurred in a surprising and positive release of pent up energy and frustration when the 12-year-old fell in with Dick Catri and Jack Murphy, a pair of surf pioneers who ran the Starlight Motel and needed a gremmie to clean the pool.

Meanwhile, Catri and Murphy had converted one of the motel’s cabanas into a crude workshop from which they were making surfboards to supplement the meager supply of boards available from the West Coast. When Gary finished cleaning the pool, he swept up foam dust. Murphy and Catri liked the tough little snapper. They taught him to surf and lent him their boards. “I started hanging out with those guys and surfing my ass off. And I loved it,” says Propper. “And I needed it because I didn’t have a father figure in my life. I was confused about who I was as a person and had no direction.”

Catri and Murphy (the same “Murph The Surf” who would soon become notorious for stealing the Star of India gemstone) may have been unconventional role models, but their influence irrevocably changed the young boy’s life path. And for Catri, at least, the fortunate change was in many ways reciprocated as Propper became one of his all-star team riders for Surfboards Hawaii, Hobie, and other labels he promoted successfully over the years.

Propper would never improve much academically, but being a surfer offered its own rewards. By age 14 he was kicking butt in local contests, and two years later he became the East Coast Junior Men’s Champion. It was an exciting time to be in Cocoa Beach, remembers Propper. “I’d train by running on the beach with the astronauts. They had balls of steel and were in great shape and pushing themselves to the limit in every way. They didn’t know if they’d be sent into space and never come back. After all, they were still sending monkeys up there at the time.”

Propper by that time was drawing a small salary from Catri’s Surfboards Hawaii distributorship, and counting among his peers and teammates Mike Tabeling, Bruce Valuzzi, Fletcher Sharpe, Mimi Monro and other top surfers of the day. “It was a star-studded team,” says Propper. “And we all got a tiny royalty on board sales. It wasn’t enough to live on but I thought, ‘that’s it. I’m going to make a name for myself and make a living out of this wherever I go.’ That’s when I really got my shit together.”

But GP had another image in mind when he thought about the style he’d most like to emulate—and he was not alone: “Everyone wanted to be like Mike Doyle. He was the guy. Everyone wanted to look like him, dress like him—tan, sunglasses, hair. He was cool, smooth—he had style. Even when he was goofy, he was goofy at the right time. He knew how to handle his fame. I could see that this guy was going to be around. That’s where I wanted to be.”

If Mike Doyle reflected the surf image better than anyone else on Propper’s horizon, it was a different matter in the water. “Other competitors hated [Doyle’s success] because he wasn’t as good as many of them—Jackie Baxter and Dru Harrison, for example—but to me Doyle was superior because he knew how to handle his fame.

When the contest horn blew, Gary looked elsewhere for inspiration: To Dewey Weber for his dynamic hot-dog style, and to David Nuuhiwa for his smooth moves, tuberiding and, of course, phenomenal skill on the nose. Cocoa Beach may have been the East Coast’s Surf City, but the real action—the contests, the media, the big bucks, the fame, the glory—were all on the left coast, in California.

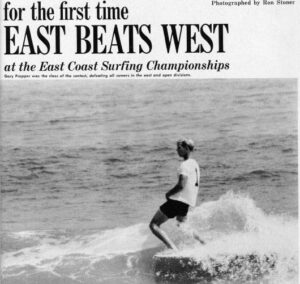

Photo: Ron Stoner

“When I first brought these kids to California, they were not as good as the Californians, but man, they learned fast,” explains Catri, who was responsible for Gary’s first visit to Mecca. “Propper, with his athleticism, was hungry. He was always on the move, trying to do something—anything—that was different. Claude Codgen was the stylist and his eyes were open wide; he was able to do everything Propper did, but cleaner and smoother. Mike Tabeling, one of the most talented surfers we had back here, watched and absorbed everything. Each one of them knew how to surf, they just needed to learn how to surf in California’s backyard.”

On that first team trip, Propper was amazed at the California surf scene and found the waves “unbelievable”—especially those he encountered at Swami’s and Trestles. “I thought California would be just like Florida without the AC,” he laughs. “But the surf was so good. And consistent. And the kelp kept the waves glassy all day, even when the wind was onshore. I couldn’t believe it.”

Propper quit school the following year and moved to California. “I’d only been hanging in there [high school] because I was gaining notoriety and I liked the girls,” he laughs about his status as a Cocoa Beach High dropout. He was just 17 years old.

What happened next depends on who’s telling the story. Propper himself says the idea was for him to “just surf and impress John Price and Surfboards Hawaii, and Don Hansen, because Catri had it mind to do some deals with those guys about East Coast distribution. That was the plan we sorta had…”

Propper checked into the Biltmore Hotel in Long Beach and stayed several months, surfing Hermosa Beach, trying to build a rep, and schmoozing most of the key local boardmakers, including Gordon and Smith, Dewey Weber, Jacobs, and Greg Noll. Gary remembers them being in a “bidding war” for his talent and signature model.

Others say he bounced from shop to shop, getting free boards wherever he could, then selling them before moving on to the next sponsorship deal. Whatever the reality, Gary eventually wound up at the leading shop of the day. Hobie Alter recalls it well: “He came to us a bit of a bad reputation. He was an aggressive guy and still just a young kid, but he was a good surfer and rising in popularity really fast. We already had a Corky Carroll model and a Phil Edwards model, and we wanted something for the East Coast, and he was the first from that area to really get noticed.”

Propper credits Terry Martin and the Patterson brothers, all of whom were core Hobie shop personnel, with giving an East Coaster the essential personal introduction to Hobie’s inner sanctum.

“Terry made something happen because he was the most easy-going out of all those guys,” Propper remembers. “I knew he was a master shaper and told him ‘Hey, you may not believe it, but back home I’m what’s happening and I’d love to go catch a few waves with you.’ Most of the California guys wouldn’t even go surfing with me back then. But Terry did. And he told the Patterson brothers ‘Hey, this kid’s hot.’ So they came down to the beach to check me out. Now, I knew these guys loved their beer, so I bought ’em a six pack and they drank that. Then I bought ’em a case and they drank that. Then we all went surfing together.” And thus a lucrative and longstanding relationship began to blossom.

“Gary had always been a hustler,” says Hobie Alter. “But with us, he worked really hard and was always really responsible about whatever he did. Really loyal. Corky, Phil, and Gary were all active with their signature models, from the board design itself to the ads and promotions. We never had an ounce of problem with Gary. He and I got along great.”

There’s a pause as Hobie remembers another aspect of the Propper persona: “He was never afraid to speak his mind,” he says thoughtfully, as if trying to be diplomatic.

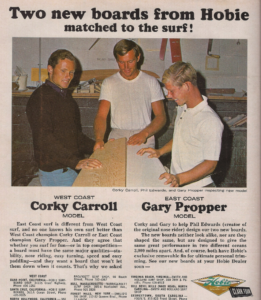

In the first SURFER Magazine ad for Hobie’s Gary Propper model, the Cocoa Beach newcomer shared a page with Corky Carroll. The concept was “the right board for each coast,” and the two hotties looked relaxed and comfortable together laying out their templates on a blank. Corky was not stoked, however. “He and I didn’t get off on the right foot,” Corky remembers. “Hobie came out with our models at the same time which sounded alright until I figured out that about 98% of all boards being made were sold on the East Coast!” And then he adds, laughing. “It all worked out okay. Over the years we both made a lot of money. But Gary was the East Coast and I was the West Coast and Hobie definitely pitted us against each other.” (The two surfers eventually became good friends and remain so to this day. In fact, when Propper optioned Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles he hired Corky as a consultant to the project: “I wanted them to talk like him,” he explains.)

Surfer and Hobie shaper Mickey Munoz also remembers the prickly rivalry. “I was already dealing with Corky,” he says of the time Propper arrived on the scene. “Corky was really cocky. And GP was exactly the same way. But there was still a kind of sensitivity there and I think I liked him. There was a certain amount of jealousy among all of us, though—who was this upstart invading the West Coast? I was a little older and probably more tolerant. Corky was more affected. But I sure shaped a hell of a lot of Gary Propper Model boards.”

Munoz mostly did the Propper speed shape model, aimed at Puerto Rico—up to eight boards a day during the peak years. Terry Martin and Ralph Parker also mowed foam that ended up with a Gary Propper laminate and, as Dick Catri remembers, during one 12-month period in the mid- ’60s, Propper made $35,000 in royalties—a small fortune back then, representing what many people believe to be the most signature models ever sold by anyone in such a short period of time. Much of that has to be attributed to Gary’s personal involvement in setting up dealerships along the entire Eastern Seaboard. “I loved getting in my van and driving up the coast,” he says, still relishing the memory. “I loved calling on the shops. I loved all those little beach towns and I had ’em all wired.” Propper’s voice trails off as reverie takes over and he runs through a barely audible itinerary that concludes: “Ventnor, Margate, Atlantic City, Rockaway Beach.” Then he’s back in the present, saying, “Not that I didn’t dig California, but I could never make any money back there!” Nevertheless, Proppers life was bi-coastal from then until the ’70s. “I’d spend winters in California and Puerto Rico and summers in Cocoa Beach, because that’s where the business was,” he says. Except of course, when a contest called him away.

As a competitor, Gary was peaking, but the personal highlight remains a 1966 event at Canaveral Pier (editor’s note: This event was actually at Virginia Beach) where he beat Dewey Weber before a wildly enthusiastic home crowd. “Dewey had been my idol, but I was ready to beat him because he was older than me and he’d already had his time. He was done,” says Propper.

Propper in top form beats the best. Surfer Magazine 1966

Of course, Propper was not the sole East Coaster making waves during the mid-’60s. “I was pumped and all my mates were pumped,” explains Propper. “Claudie [Codgen], Tabeling, sure, but Dickie Roseborough, Joe Roland, Bruce Clelland—all these guys most people have never heard of. We built our own team. We had guys who’d been surfing only one or two years and were already competing—they were into it.” And, Propper acknowledges, “When Catri was on his game in the ’60s and ’70s he was a great coach, a great motivator, a great captain. He influenced everybody. He made us fanatics out of all of us!”

During the period between ’65 and ’67, Propper surfed in as many big contests as his calendar made room for, most of them in California, and he earned a reputation as a formidable opponent. “But it was hard,” says Propper. “There’d be five or six events in a row and those guys in California were fucken good. And they had good waves to ride, not the crap we were surfing in Cocoa Beach. But Catri always told us that under the right conditions we could beat any of those guys.” As far as Gary was concerned, “those guys” included Jackie Baxter, David Nuuhiwa, Cheer Critchlow, Dale Dobson, Dru Harrison, the Leonardo brothers, Sparky Hudson, Rich Chew, Donald Takayama and Herbie Fletcher—an interesting list for anyone trying put perspective on an era when media coverage, based then as now in southern Orange County, had a distinctly parochial agenda. (When SURFER Magazine gave Propper a chance to do a “Tips” column, for example, his topic was not about the technical excellence of his noseriding, his cutback, or his winning strategies for contests. It was on “Riding Junk Surf.”)

photo: Ron Stoner

Hobie surf team, East coast Surfing Championship, 1966 Photo: Ed Greevy

“Tabeling and Codgen both had more natural talent than I did,” continues Propper. “I had to really work at it. But I was very disciplined. Plus I loved everything that went along with being a big name surfer. I liked designing my own tee-shirt, my own boards, I liked the ad campaigns. A lot of guys weren’t into it. But I was into it then just like I am today promoting Gallagher or Carrot Top. I like making something happen that otherwise wouldn’t be.”

If the East Coast crew lacked the natural resource of waves that the Californians enjoyed to their advantage, they made up for it by hitting the road. “Everyone started to travel,” recalls Propper. “First it was Puerto Rico, and that opened up the floodgates to Central America, South America. That’s when East Coast surfboard manufacturing really started up. Suddenly there were new markets. That led to new East Coast-based shapers—Codgen, Tabeling. And they influenced Greg Loehr, Jeff Crawford, who in turn passed it down to Kechele and the guys today.”

The same, he says, is true of the legacy of champions that Florida has produced, from himself and Mimi Monro, on down to Kelly Slater and Lisa Anderson. Propper swells with emotion when he speaks of his own achievements and the records laid down by subsequent generations. He is proud of the role he may have played in it: “I always loved it that kids would want to come hang out at my house,” he says. “I was such a grem and a motherfucker, and still am. I wanted to inspire them.”

Not all of Propper’s surfing efforts were successful, however. His first experience in Hawaii, for example: “It really freaked me out,” he says, recalling his trip to the Islands for the 1966 Duke Kahanamoku Invitational. “From the minute I looked out the plane window and saw the waves, I knew I was dead. It was huge the whole time I was there. It was 20′ for the Duke and I had to paddle out. It was the first time I’d surfed in Hawaii and I didn’t have the right boards. Brewer and Hynson were making guns for everyone and they wouldn’t even make me one. They said, ‘Oh, you’re an East Coaster, you wouldn’t be able to ride them properly.’ There was a whole pecking order for who could, and who could not, have one of those boards. So there I was, a champion surfer, and I didn’t do good. When I came back home everyone was really bummed out.”

Today, Propper remains stoic about that initial Hawaii experience. “I had a real fear of big waves,” he says. “I didn’t get into big waves until the mid-’70s when I was past my prime. I just wasn’t into it. And you know what, whether or not they’d admit it, a lot of other guys felt the same way.”

Still, Propper continued to hold a place in the top echelon of surf competition and was a tireless promoter and marketer of his boards until the shortboard revolution. While Propper says he “loved the shortboard thing” and made the performance transition without missing a beat, he was suddenly regarded as part of the longboard era—a marketing anachronism. Plus, he says, when the design paradigm shifted so suddenly, “Hobie just wasn’t ready for it.”

“It didn’t happen right away, but it was all over for me as a surfer,” he reflects. “When you’re at the top of your game there are always lots of people who want to see you eat it. That’s just how things are,” he says, with no hint of bitterness. “It’s not that I was tired of surfing, but I was tired of being a champion. It’s like I’d had all this recognition and then suddenly I had none.”

At a crossroads in his surfing career, Propper also suffered a huge emotional blow—his wife took off with a surf photographer Gary had hired to a photo shoot. “I couldn’t believe it,” he says. “It was like all the layers of my whole life as a surfer were cracking. I was pissed at [the guy] because I really dug that chick. I was pissed I couldn’t make the shortboard transition work with the same flow I had on the long boards. I felt I was still rad but the shops weren’t there anymore. There was no more room for anything ‘old.’ I was pissed at the surf industry: ‘How dare they do this to me?’ I was pissed at Hobie—’fuck Hobie,’ that was where I was at. I was looking to get my ass into a new gear, pronto. I wanted to do something different.”

Propper had laid a foundation for what was to come. With his natural talent as a promoter, he already had plenty of experience publicizing surf movie tours of the East Cast—coordinating the poster runs and radio spots that result in cash at the box office and bums on seats, all of which began when Jamie Budge asked him to become a partner in a series of movies he made and took on the road from the mid-to-late ’60s

In 1970 Propper teamed up with longtime friend and musician Kenny Cohen to stage a show featuring surf movie footage and a live band at the Surfside Playhouse in Cocoa Beach. As Sam Hawk and Owl Chapman tackled Pipeline on screen, Kenny’s band, The Fantastic Group, rocked out on acid. “People freaked,” says Propper, breathless at the memory of the crowd’s reaction. “They fucken loved it.” The success of that event (and several more that followed it) inspired him to pack up and move to West Palm Beach to become a full-time assistant booking agent with John Valentino and John Stoll at Fantasma Productions.

Michael Lang, Joe Cocker, GP Photo: Ken Davidof

Working as a promoter in the entertainment industry was ideal for someone with his background, Propper says. “Not so much with the bands, because they took one look at me—a surfer—and copped an attitude. But I loved Palm Beach and I loved the money. I’ll be right up front about it: When I saw all that Palm Beach old money in the hands of such stupid fucks, I said to myself, “I’m gonna get me some of that.’ I was ready to kick some major butt.”

It didn’t happen right away, though.

“It was seven and a half years before I got an act to represent and began promoting outside of Florida,” explains Propper. “So I started by promoting bands, concerts, and clubs like Rickie Dee’s, O’Hara’s, Dante’s Den, Hots Nights of the South.” But he did not leave surfing behind entirely, and in West Palm he hooked up with Fox Surfboards’ John Parton and started riding and promoting his boards. “They had all these groms on their team and we killed. I was a big name on the team, and while I didn’t have a model or anything, I did sell lots of boards.”

But it was the entertainment industry that Propper wanted to excel in. Musician, composer, session man and producer Kenny Cohen, Propper’s longtime friend, says Gary was a natural. Even though he was a surfing success, says Cohen, “He just woke up one day and said ‘is this all there is?’ He’s gregarious, aggressive, and has this ‘I can conquer the world’ attitude. He’s always totally up to date with the latest music—he’s always turning me onto something new. Plus you’ve got to remember, this is the south and there’s a lot of guys around here who aren’t real bright. Gary’s always defended himself admirably. When you’re blonde and cocky and young and the girls are hanging off you, there are guys around here who just want to kick your ass. But Gary can be a bad little motherfucker. He networked himself against all odds into the Hollywood entertainment scene. Usually, if those people find out you’re a surfer from Florida, no matter who or what you might be promoting, they’d just tell you to go home.”

CarrotTop, Evonne Propper, GP

Today, “home” for Gary Propper is a complex concept and most of the time, when not on the road with Carrot Top, he can be found at his condominium in an upscale Pacific Palisades gated community, close to where Sunset Boulevard meets the ocean in Los Angeles, or at his oceanfront house in Satellite Beach, Florida, or on his rambling property on Maui—a place he bought after Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles hit big in the early ’90s and he could afford to take some time to kick back a little and surf a lot more once again. He never quit surfing, though, even during what he calls “the Gallagher days, when it was something I could do less frequently than I’d have liked.”

The intense surf resurgence of the Maui period lasted some six years. During that period, he and his longtime surf buddy and shaper David Balzerak (“DCB”) reclaimed a rundown property from the jungle that was consuming it and renovated the home that languished beneath the predatory tropical plant life. His surf fever faded only when a back injury forced him to slow down, even to stop for a while. By then, however, he’d already become involved and had two daughters with “a blonde knockout” he’d met at the LA-based William Morris Agency. “We moved to Maui together and we broke up a million times,” he says, sighing over the turmoil and trouble that often brews beneath the joy and passion shared between the sexes. The two are now separated, but she and the children are still obviously important to GP, as is the girlfriend and daughter in Florida whose telephone number turns up on the long list of many places GP may be found at any given time.

Gary Propper is fiercely loyal to his surfing roots. Whatever he does in showbiz, he says, he always manages to find a way to slide a surf image into the production or collateral publicity materials, and, he says, he tries to work with or hire surfers whenever he can. His greatest wish today, he says, is to see a top surfer become a major Hollywood star and-or heartthrob. “Vince Klyn is about as close as it’s come,” he says, “But there are a lot of guys who could do it, and I can’t wait for it to happen. Laird Hamilton, for example, could be the next John Wayne. There are plenty of others: Donovan Frankenreiter, Brad Gerlach, Dino, Kelly—they’re all great guys who can really turn it on in the water. They just have to know how to do that in Hollywood—and be as consistent about it as they are in the lineup.”

One gets a distinct impression that achieving this goal may be Gary Propper’s next major project.

Gary Propper died in his sleep on March 14th 2019

Why isn’t his first wife Ruthann mentioned in this article? She was his soulmate who worked diligently with him on all his entertainment enterprises not that Hawaiian Tropic chick. He had another beautiful girlfriend he loved who he was with for a few years mid nineties on Maui that he moved to Sebastian Inlet with as well. He married again to a different woman Evonne in the late nineties too who had his son Dylan. This story seems to be contrived in this regard. Regardless he was an epic surfer!

The article was published first published in 1999 so it was not meant to be an up-to-date history of Gary.

Sorry for the delayed answer but we have been having website issues.