Article by Justin Housman. Re-printed from Surfer Magazine, May 30, 2016

When duty called in Afghanistan, Captain Nate Dinger took his love of shaping with him.

If most surfers learned that they were about to be sent to a landlocked, militarized war zone, their first thoughts would likely lie somewhere along a spectrum of disbelief, with “Oh shit” on one

side and “There must be a way to get out of this” on the other. Missing surf because of a regular nine-to-five job is terrifying enough. Getting shot at in war-torn desert? Surely you’re joking. Yet when Nate Dinger, a National Guardsman from St. Augustine, Florida, learned that he’d be deployed in 2015, a far more sensible thought came to mind: “How the hell am I going to get surfboard shaping supplies in Afghanistan?”

It was a good question.

Dinger (who goes by the brilliant name “Nate Danger” on Facebook) is a captain in the 1-265 Air Defense Artillery Battalion. His unit operates the Avenger—basically a modified Humvee with attached missile launchers that looks like it would be GI Joe’s vehicle of choice. It provides air defense for ground troops against pretty much anything that flies. Prior to his shipment to Afghanistan, all of Dinger’s previous deployments had been in and around Washington, D.C., fending off any potential airborne threats to important government installations. Needless to say, there weren’t many, save the odd disgruntled postal worker piloting a homemade helicopter onto the president’s lawn. Heading off to Afghanistan, you might imagine, was a bit of a change, and a real pain in the ass for a guy who’d just started shaping his own surfboards.

Born in Lexington, Kentucky, Dinger moved to St. Augustine with his family at age 12. He taught himself to surf during family trips to the beach as a kid, and by his early 20s, Dinger had grown into a “full-on long-haired surf rat.” Which made his decision to join the National Guard all the more surprising to his parents and friends.

At the time, Dinger had a full-time job manning the deli at his local Publix grocery. He had designs on management and buying a house in the area. But Dinger, the son of a Marine Corps veteran father, felt compelled to enlist in the military shortly after watching the World Trade Center go up in flames on 9/11. “I couldn’t just sit around wondering if there was something I could do about what had happened,” Dinger says.

It wasn’t long into his military career that Dinger found out he’d have the chance to do that something: The U.S. invaded Afghanistan while he was in basic training. “Our drill sergeants grouped us all together one day and told us that we were at war and that we should expect to be deployed,” Dinger says. “It wasn’t a surprise. You don’t sign up expecting not to go.” Fortunately for Dinger, it took quite a while for his unit to be called to the front lines. In 2014, Dinger was informed that he’d be shipping out to Afghanistan roughly a year later. This gave him just enough time to come up with a plan to bring his newfound love of shaping with him to the base. He’d only recently begun making boards and was determined to not let his skills wane while he served overseas. Plus, Dinger wanted something familiar to take with him into the desert.

“I’d heard that deployments to the desert can feel like being trapped in a never-ending maze,” Dinger says. “To deal with the monotony and loneliness that I knew was coming, I had to figure out a plan to bring shaping to Afghanistan. It was the only way I’d make it.”

His first step was to gather everything he’d need to make boards—shaping tools, resin, fiberglass, the works—and leave them with his confused wife to ship to his base via freighter. He bought blanks, carefully packaged them up and had his wife send them over too. There were logistical challenges. Getting the resin through military customs was difficult. You won’t be surprised to learn that shipping volatile chemicals into a heavily guarded, munitions-packed army base isn’t a simple affair. But Dinger’s supplies eventually arrived intact after crossing the Atlantic Ocean, part of the Indian Ocean, and traveling overland across Pakistan.

Dinger enlisted a few interested soldiers on his base to help him track down a vacant shipping container that he could use for a shaping shack. He outfitted it with a generator, scrounged up lighting, and slapped together a board rack from old pallets. Eventually he flipped the power switch, the lights flickered on, his planer zoomed to life, and Captain Dinger was making surfboards. On an army base. In the middle of Afghanistan.

Because he was busy all day with the far more important task of maintaining the defense systems that helped protect the base, Dinger had only about 45 minutes each evening to work on his boards. And even during those short windows, the fact that he was in a war zone was impossible to ignore. Rockets and mortars fired from nearby Taliban positions occasionally whistled over the base and were intercepted by defensive countermeasures, the sky often crisscrossed with tracer rounds, soldiers everywhere hitting the deck.

But Dinger, aided by his friend B.J.—who doesn’t even surf—kept right on mowing foam, laying glass cloth, and sanding, all the while battling to keep Afghanistan’s impossibly fine dust from infiltrating the shaping shack. “Every night, B.J. and I focused on one small aspect of board building,” Dinger says. “We planned out the steps we’d work on in little chunks.”

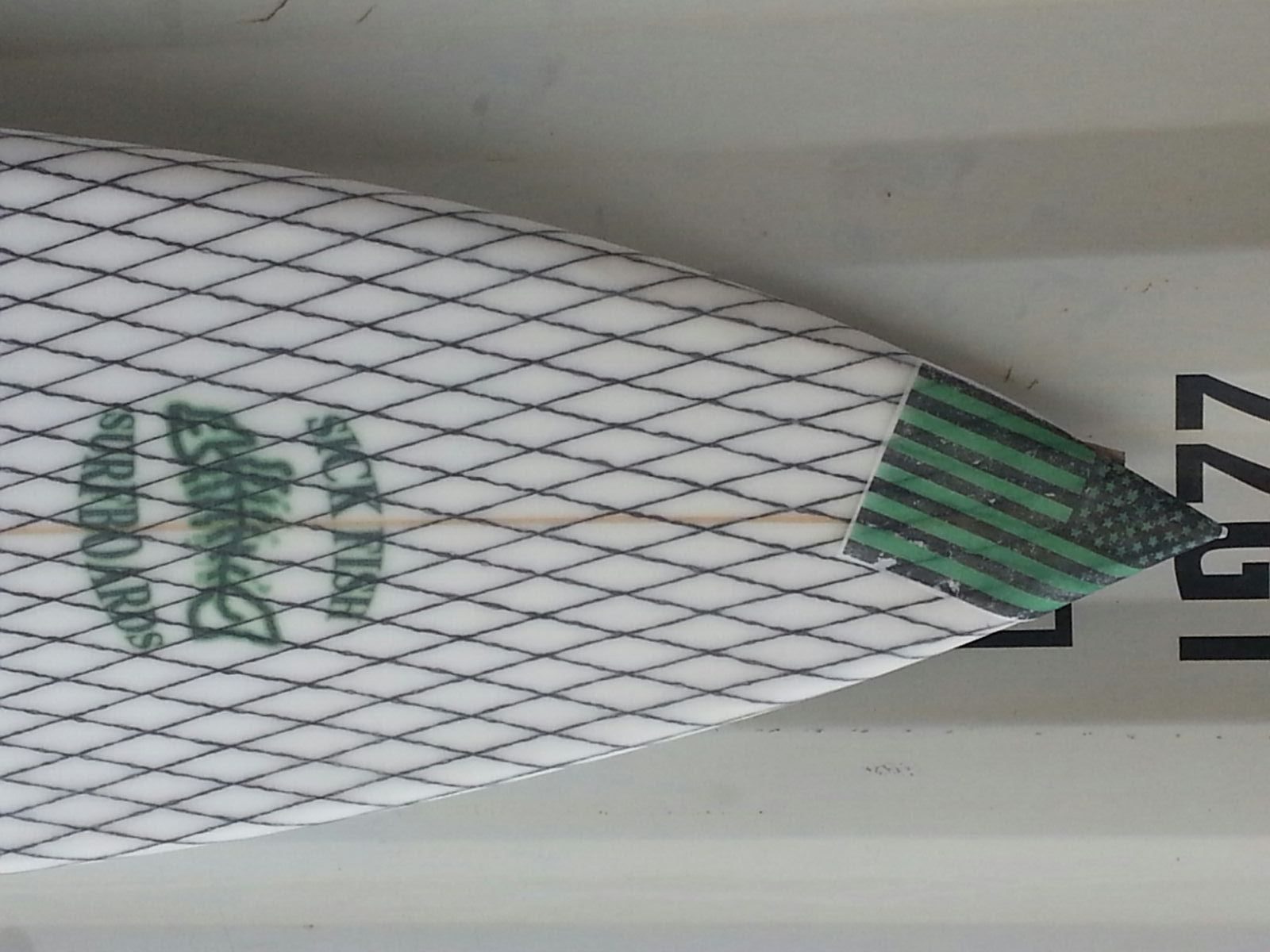

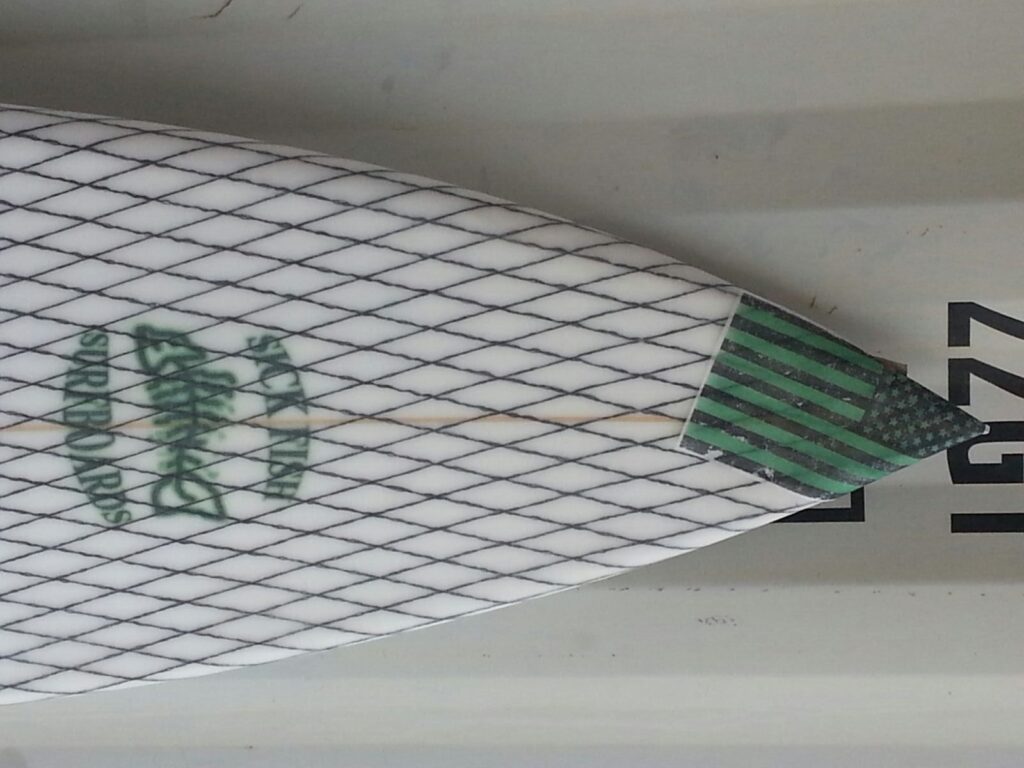

Finally, after weeks of getting his supplies in order, shipping them halfway around the world, finding a space to work, and dodging the occasional shower of rocket fire, Dinger had built his first board: a 6’5″ thruster, complete with a custom-designed “Sick Fish” logo. Certainly no surfboard has ever been built in a more unlikely environment.

Dinger and B.J. eventually made three surfboards. A few guys in Dinger’s unit surf regularly (enough soldiers on the base surfed that copies of SURFER were sold in the base’s PX store), and they’d occasionally poke their heads into the shaping bay, give the boards a once-over, and talk a little surf story. Dinger’s plans to improve his shaping technique, and to lean on board building as a way remain sane in the face of extreme mental hardship, worked flawlessly.

Dinger’s tour ended in February and he was eager to actually ride one of his creations back home. Nervously, he wrapped up his most improbable of Afghanistan souvenirs and sent them back on the same freighter journey his supplies had taken to get to his base. Two of the boards survived the trip without a scratch; one suffered a massive ding. “Two out of three ain’t bad,” Dinger says, proudly and with unmistakable relief. “And hey, the boards work!”

Leave A Comment